It’s always an interesting discussion with non-technical people involved in contracting for power supply. Energy contracting is oftentimes the responsibility of personnel who are not familiar with the price dynamics of the power markets. The conversation will typically start with “we use a lot of electricity…..we should see a great price”. While that may be true, it’s not necessarily the magnitude of usage that drives the price, but the consistency and level of demand. What’s the difference between demand and usage? Power demand is the amount being drawn from the grid at any point in time; usage is the aggregate of demand across time. A consistent or flat demand profile, meaning a higher load factor, will command a better price than that associated with a low load factor. So why is that?

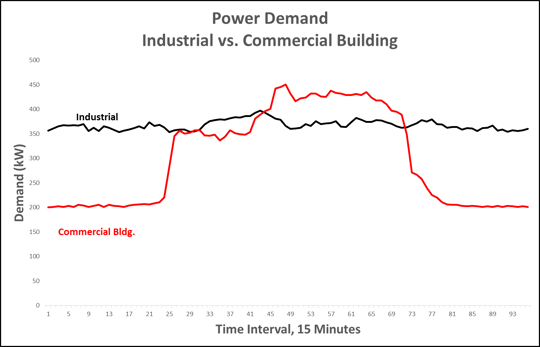

The chart below reflects the level of demand over 24 hours, for two different types of power consumers: a small industrial facility and a commercial office building, on the same day. The industrial facility’s power demand is obviously driven by production, while the office building’s demand is influenced mainly by weather, occupancy and the efficiency of its air conditioning equipment and controls systems.

Power usage is somewhat higher for the industrial facility than for the commercial building, but it’s the attractiveness of the industrial facility's high load factor that incents the supplier to offer a better price to the industrial consumer.

For the power supplier, it’s all about cost and managing risks. Their costs include the power they must purchase on the wholesale market, the costs they must pay to the grid operator to deliver the power to the customer’s meter and the costs associated with volumetric and credit risks. The power supplier can realize a very “clean” hedge for the wholesale power if the consumer’s load profile is sufficiently high and flat. The most transparent and liquid market for wholesale power trades in a “block” of 5 business days by 16 on-peak hours. For demand outside those parameters, in other words the demand beyond the typical minimum or base usage, the power supplier will pursue a less efficient means of hedging their power buy, including limiting, by contract, the variability the consumer can have in their power demand and usage in comparison to either historic or stipulated levels. These “dirty” hedges are not only less efficient, but less effective, requiring the power supplier to tack on volumetric risk premiums to the price offered to the consumer.

So what’s our take away from this? As a large power consumer, understand your load profile and search for ways to improve that profile by reducing or flattening demand within the flexibility of your operations. For a commercial building, that means utilizing the building’s controls systems more effectively, which requires no capital expenditure, or installing more energy efficient equipment. For the industrial consumer, strategies for improving the load factor may include shifting production from peak to off-peak times, staging certain equipment start-up, or rationalizing base demand so that power usage during times when the plant is not producing goods is minimized.

These strategies will result in a better price for power.